The nostalgic power of

landscapes continues to hold billions of people in an unrelenting grip. We are

all born into natural and cultural environments that shape what we become,

individually and collectively. From our "mother tongue" to our father's faith,

from medical risks to natural hazards, the place where we start our journey has

much to do with our destiny, and thus with our chances of overcoming the

obstacles in our way. In this

respect, the power of landscape is expressed as memories unassailably attached

to our first home surroundings and subsequently it may be transferred to other

landscapes to which we become addicted for our

holidays.

'Landscape',

'landscape-specific thinking', and 'landscape-making' are not new concepts in

contemporary practice, but terms such as site, space, place and landscape are

often used interchangeably. Philosophers throughout time have wrestled with the

concept of landscape before the term was invented when trying to define the

nature and extents of our spatial existence. So it seems presumptuous to assume that

the elements of 'landscape' would be the same for everyone.

In trying to define

our place in space, it is essential to comprehend that the body's relationship

to landscape exists on several levels including the physical and the cerebral as

well as individual perception and perspective in relationship to other objects .

Yet, landscape is not defined merely by a person's physical and psychological

relationship to space. Landscape is also a compilation of an individual's

cultural and emotional connection to a particular space. While exploration of

the physical and analytical need for humans to develop a relationship to space

helps to define the power and necessity of landscape as a concept, it is the

cultural and emotional needs that form the foundation for understanding that

creates a sense of landscape. To paraphrase the contemporary philosopher Edward

Burtynsky,

"We do not live in

space. Instead, we live in landscapes. So it behoves us to understand what such

landscape-bound and landscape-specific living consists in. However lost we may

become by gliding rapidly between landscapes, and however much we may prefer to

think of what happens in a landscape rather than of landscape itself, we are

tied to landscape undetachably and without

reprieve."

Our emotional and sometimes idealistic attachments create values for aspects of landscape through our personal memories and associations. Yi-Fu Tuan, a geographer who is often referred to as one of the founders of humanist geography, refers to such attachments to landscape as topophilia, or love of a landscape, which he defines as the relations, perceptions, attitudes, values and world-view that effectively bond people to place. Each individual relates to the environment around them in varying ways, with differing intensity, and these bonds and connections derive from different sources. Yet, at the most basic level, we learn to love what has become familiar. This phenomenology of landscape can be expanded to a cultural level when the attitudes, views, and values become a collection of shared social references and beliefs. Moving out from the individual to the community, which functions as an emotional and analytical collective, value can be landscaped on specific locations that hold significance for groups of people. This is particularly true of the otherworldliness of standing stones in the British southern downland, which was such a magnet for artists such as Paul Nash.

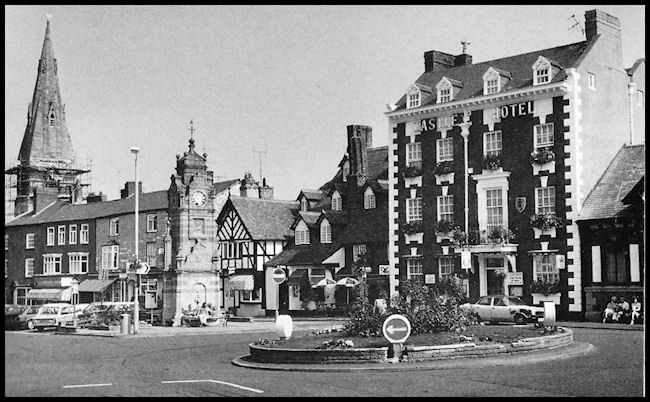

Market place; Ruthin